If you pay much attention to higher education or workforce training, odds are you’ve seen excited talk about the promise of microcredentials. Earlier this year, a survey of employers reported that 95 percent think it’s a good thing if their employees are earning microcredentials. More than 70 percent said that microcredentials have helped their organization fill skills gaps, that they’ve helped improve their workforce quality, and that their organization is increasingly more willing to consider these types of credentials in lieu of four-year degrees.

At the same time, the survey conducted by Collegis Education and UPCEA (the association for college leaders in continuing education) raised some cautions. Seventeen percent of employers said they were concerned about irrelevant credentials and a lack of critical training, and 12 percent expressed worry about the quality of the education provided.

All of this introduces a bunch of questions, the most important of which may be: What the heck is a microcredential, anyway?

Well, employers want to know whether an employee has learned a particular chunk of knowledge or set of skills. Microcredentialing is a way to more precisely deliver and track just those things. Microcredentials are typically offered as a series of short, focused, stackable, week-long courses. The most popular microcredentials tend to cover marketable skills in high-demand fields like IT support, data analytics, and cybersecurity.

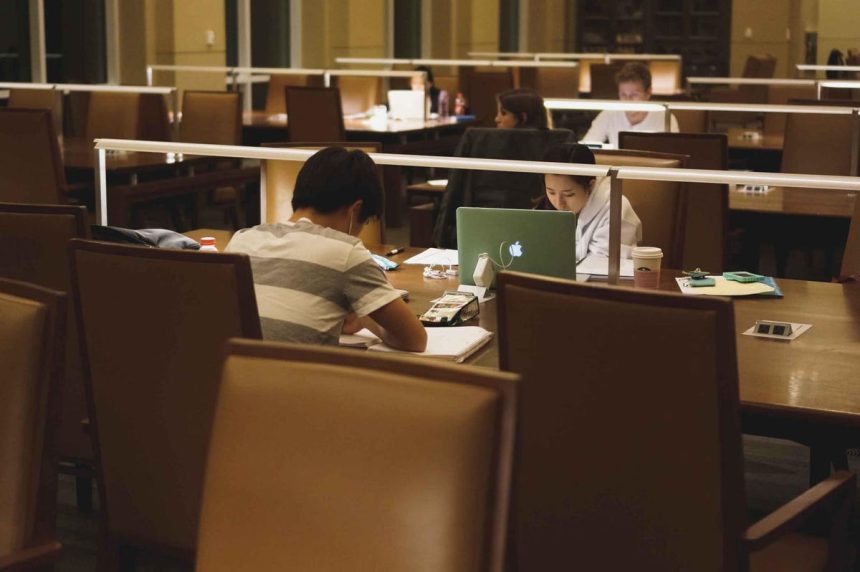

These week-long courses are notably different from the typical college experience, where students take a course by attending class for a semester and their college then bundles these semester-length offerings into credentials. This means that degree-earners frequently sit through a lot of courses they don’t want or need, while employers seeking particular skills have to wade through a lot of extraneous stuff.

In one sense, nothing about microcredentialing is really all that new. Community colleges and industry certification programs have been doing versions of this for a very long time. What microcredentialing may change is the scale and scope of things. New technologies make feasible a more bespoke, robust, and employer-friendly market, with a massive number of increasingly hyper-specialized credentials that may be especially well-suited to the speed of an information economy.

Today, Credential Finder lists more than 45,000 credentials offered by more than 2,000 organizations. And this is only a small slice of all the credentials on offer. No wonder employers are both intrigued and concerned. After all, there are many questions that need to be addressed: How does one know which are valuable? How do employers know which ones to take seriously? If employees are paying to earn credentials, who will reliably monitor and track all of this?

Given all of this, it’s an open question whether microcredentials will prove to be anything more than MOOC redux. A decade ago, there was a chorus of voices insisting that massive open online courses would “revolutionize” education. They didn’t.

MOOCs, though, sought to expand access to college courses, in the hope that lots of non-students wanted to sit in front of their laptops and learn from college professors for fun or profit. After an initial flurry of interest, it turned out that they didn’t.

What’s different about microcredentials? Well, while MOOCs sought to make existing college courses more broadly available, microcredentialing promises to offer focused, timely training that addresses a precise, practical need. Whether it will deliver on that promise is, of course, a bigger question.

There’s reason to think that microcredentialing could deliver. New technology has made it increasingly feasible to deliver this kind of customized instruction, to assess mastery, and to track an individual’s microcredentials (the caution is that there’s a pretty big gap between its feasibility and actually doing these things). A graying workforce means the need for ongoing, customized skill acquisition will only grow. And just-in-time, stackable credentials seems well-suited to a nation increasingly used to tailored offerings and coping with big labor-market shifts.

Ultimately, it’s hard to imagine how workforce training or higher education can become more customized, timely, and affordable without some form of microcredentialing. But that will require clearing a series of high hurdles, including changes to federal funding rules, accreditation processes, hiring practices, and much else. It’s easy to appreciate why employers would express both hopefulness and hesitation. There’s good cause for both.

Read the full article here