Italian Francesca Bellettini was appointed second-in-command a few days ago at the Kering group, the 20 billion Euro luxury holding led by François-Henri Pinault. The Italian manager, capable of multiplying Yves Saint Laurent’s turnover by six, taking it from 500 million to 3 billion Euro, will therefore play a key role in the group which owns, as well as YSL, Gucci, Bottega Veneta, Balenciaga, Pomellato and Brioni, among others. The stock value celebrated this new order by rising, thus giving credit to the ability of the Italian manager, the first woman to occupy a role of this kind.

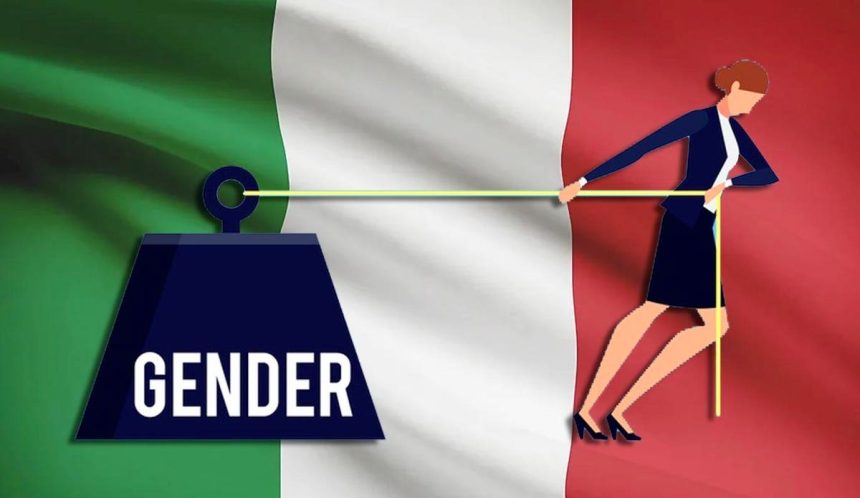

Is this then a golden moment for Italian women, with Georgia Meloni head of government, and Elly Schlein leader of the opposition? Unfortunately no, as data from the classification compiled on the Gender gap each year by the World Economic Forum testify: over the last year, Italy has actually jumped back from the 63rd to the 79th place, right behind Uganda. We have been penalized by a worsening in our performance with respect to the political empowerment of women. The rise to power of Georgia Meloni has not led to an increase in female representation in the government and in Parliament. Rather, female ministers are actually fewer than in Draghi’s government. The same happened in Parliament, where last year only 186 women were elected out of a total 600 Members. The absolute figures are not wholly significant, given the law that reduced the number of components of the two chambers, but the percentages speak out clearly enough: there are now 31% women compared to 35.3% in the previous legislature. And this is the first time, since the elections of 2001, that the percentage of female parliamentarians has diminished from one legislature to the next.

This fact quite frankly fails to surprise. Because, apart from affirmations of principle and generic support for the equality of the sexes, Italy remains a country of profound and convinced misogyny. This is clearly evident in various expressions of daily life: in these days we have received news of the national television commentator at the World Swimming Championships in Japan, who was hastily recalled to Italy after having made shockingly sexist comments during the female diving competition. But we could equally recall the comments made by the Under Secretary for Culture Vittorio Sgarbi during a recent official event.

Even more worrying are signals coming from the judiciary, whose reaction to certain types of crimes can also only give the measure of the level of general acceptance towards these phenomena. A janitor accused of sexual harassment of a minor female student was found not guilty because he felt her “only for a handful of a seconds”. In a recent sentence, whereby a man was condemned for having hammered his partner to death and then cutting her up, to 30 years in prison, and not given life, because, behind this gesture there was the idea of “having lost staple contact with the woman with whom he was desperately in love” and the frustration for having been used by her and set aside. According to the judges, the man had realized that “the uninhibited young woman had in some way made use of him”, inciting the murder. This being nothing more than “a way to get out of this unbearable condition of uncertainty and suffering set off by the decision of his stimulating beloved to abandon him”.

When faced with motivations of this kind, the choice of words (“uninhibited”, “stimulating”), the justification for the murder in the woman’s decision to leave him, there is, indeed, very little hope. If this is the judicial culture that reflects and produces the general culture of a country, the path towards equality of gender that Italian women have to pursue is still a long and arduous one. Very long and very arduous indeed.

Read the full article here