Words — from both Beijing and corporations — sound sweet, but reality is less encouraging. Beijing says that it is open for business and that it welcomes foreign investment but has made doing business in China more difficult than ever. Corporate executives speak of engaging China and then send their dollars, yen, euros, pounds, won, and whatever elsewhere. The situation is hard on all involved but promises to go hardest on China.

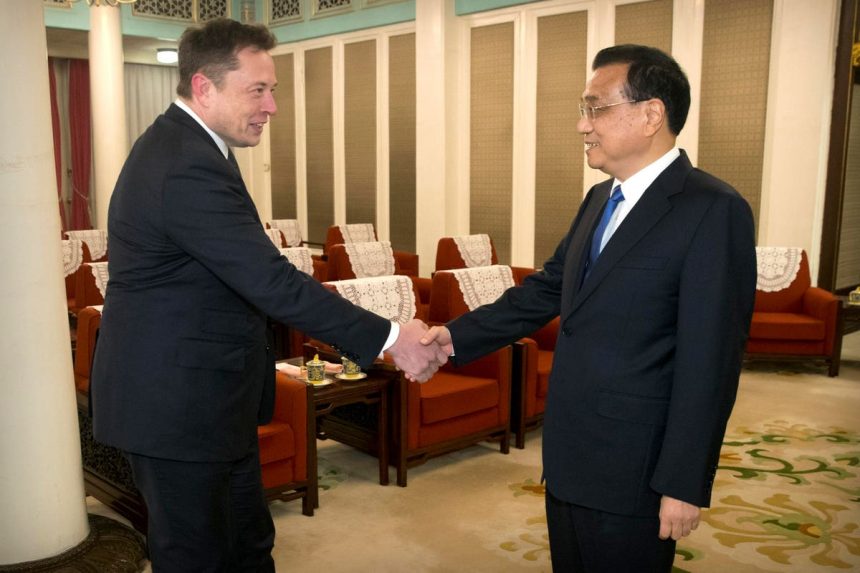

If one just listened to official pronouncements, trade and investment prospects would look strong. Chinese Foreign Affairs Ministry Spokesperson Mao Ning insisted recently that China “welcome[s] foreign companies to invest in and do business in China, explore Chinese markets, and share in development opportunities.” She added that “China is firmly committed to advancing high level opening up and fostering a market-oriented, law-based, and internationalized business environment,” From the corporate side, J P Morgan CEO Jamie Diamon called for “real engagement” between the United States and China. Elon Musk, who owns a Tesla factory in Shanghai, shared with Chinese Foreign Affairs Minister Qin Gang his abjections to a decoupling of the Chinese and American economies.

But reality belies such upbeat commentary. Most notable are a recent spate of raids by China security on foreign-based consultants, auditing firms, and law offices operating in China. Due diligence firm Mintz Group reports that just this past March, Chinese security agents arrived unannounced at their offices and detained five staff members. U.S. consultant Bain & Co. reports a similar raid on their Shanghai offices, although in this event staff were questioned but not detained. Chinese state media announced that security authorities were investigating the consultant Capvision Partners. In none of these events and others has official China explained its behavior beyond vague national security concerns. Speculating on the reasons, Michael Hart, president of the American Chamber of Commerce in China (AmCham China), believes it has something to do with information such firms collect as part of their business. In response to his own thought, he then asked: “How can you plan future investment if you can’t do due diligence on you future partners.”

While alone the uncertainties created by such behavior works against Beijing’s stated desire to increase foreign investment, but there is more. Beijing’s especially severe lockdowns and quarantines during the covid pandemic and in its aftermath have raised questions about the economy’s former reputation for reliability and accordingly undermined the economy’s attractiveness as a place for foreign investment. It does not help in this regard that Chinese wages have risen faster than wages either in the developed world or the rest of Asia. Further detracting from China’s allures are the tariffs that Donald Trump imposed on Chinese products coming into the United States and that Joe Biden has kept in place. All has made foreign businesspeople and investors less willing to tolerate Beijing’s policies, such as its insistence that foreign firms operating in China share proprietary technologies with a Chinese partner not to mention unexplained security raids.

Such reservations are clearly evident in surveys among American and other foreign operations in China. A recent poll conducted by AmCham China showed that for the first time in the 25 years the organization has conducted its survey China has fallen from the top spots as a preferred investment destination. Those conducting the survey summed up their findings this way: “Their willingness to increase investment and strategic priority is declining.” Similar polls conducted by the European Chamber of Commerce in China show a similar change in sentiment.

Accordingly, Japanese, Korean, and western money has sought destinations other than China. Dozens of firms have reacted to Beijing’s takeover of the once independent and largely liberal “special administrative region” of Hong Kong by decamping elsewhere in Asia, largely Singapore. Among them is Federal Express but most others are connected to the financial industry. Freight Caviar, a journal that focuses on the shipping industry, has conducted an informal survey that identifies some 70 firms that have plans to leave China for other Asian venues, notably India, Thailand, Taiwan, and especially Vietnam. Among these are the giants, Samsung and Apple. The former has completely shut down its former expansive phone factories in China and accordingly has radically reduced its workforce in that country. It is presently building the world’s largest mobile phone factory in India. Apple is planning a similar if less complete move and will relocate some operations to Vietnam while relocating its watch and iPad operations to India.

Things clearly are not going in China’s favor. Since much of the foreign reconsideration and flight reflects the actions of Beijing’s leadership, one is tempted to say that China’s wounds are self-inflicted. No doubt there is truth in that conclusion. The problem is less one of a single or even a group of policy decisions than a result of China’s authoritarian system. And from this perspective, it is hard to believe that Beijing will find a way to turn things around.

Read the full article here