We are in an age of media pointedly aimed at having iconic characters, like Barbie, reckon with past wrongs. The visuals and casting for the new Barbie movie are dazzling, but the film’s core conflict feels off, or at least askew. If the new Barbie movie is about addressing and righting past wrongs – and I think it is – the central plotline doesn’t tackle the right one, the big one. When it comes to Barbie, it’s not toxic masculinity that needs to be reckoned with. It’s Barbie’s long-time correlation with negative body image and lower self-esteem in girls.

Barbie has been thoroughly critiqued by prominent feminists like Jean Kilbourne and Gloria Steinem. Barbie has also been a popular subject of academic inquiry. In one study, playing with Barbie was correlated with girls having lower self-esteem and an increased desire for a thinner body. After Mattel released a curvy Barbie, another study done in 2019 found that girls ages three to 10 reported the larger Barbie was the one they wanted to play with the least. A paper in 2016 reported that playing with Barbie led to an increased internalization of the thin ideal among girls ages five to eight. The list of studies that show the negative effects correlated with Barbie is lengthy and unequivocal. The new Barbie movie all but brushes this list aside, instead focusing on toxic masculinity.

Get ready. Spoilers are nigh.

The Barbie movie’s plotline is teed up by the film’s byline: “Barbie is everything. He’s just Ken.” In Barbie World, there are dozens of versions of Barbies and Kens. The main characters are called Stereotypical Barbie and Stereotypical Ken, played by Margot Robbie and Ryan Gosling. We are taken on a journey where Ken’s adoption of patriarchy and eventual-yet-temporary overthrow of a matriarchal Barbie World is contextualized as a, yes, normal reaction to being sidelined and marginalized for so long. How does he discover patriarchy? He’s a stowaway in Barbie’s car as she commutes from Barbie World to the real world in order to solve an existential crisis that involves a woman named Gloria, played by America Ferrera, and her daughter Sasha, played by Ariana Greenblatt. Ken realizes that men are worshiped in the real world, which is exciting news to him. He decides to return to Barbie World without Stereotypical Barbie, and introduce this idea to all the other Kens and all the other Barbies. Margot Robbie’s Barbie returns eventually to find that all her fellow Barbies have been brainwashed.

It’s challenging to render internalized misogyny in a visual medium. I was excited to see it done so well, but I kept waiting for some of that energy to be directed toward the elephant in the room. As an older millennial, I remember playing with Barbie and Ken as a kid. Ken was an accessory, a gesture towards Barbie’s compulsory heterosexuality, and a stand-in for the man we were all supposed to grow up and date or marry. I can tell you that it was not Ken’s role in Barbie’s life that affected my body image. It was Barbie’s role in my playtime. The argument can be made that body image disturbances in girls are part of living in a culture saturated with toxic masculinity. To reduce the history of Barbie’s correlation with, for example, thinner body idealization entirely to internalized misogyny, however, is not precise enough for me.

In one scene, body image does come up. Stereotypical Barbie has just crossed over into the real world and has an interaction with Sasha and a diverse group of tweens during lunch at their school. They have strong words for Barbie, naming her part in perpetuating impossible beauty standards as one of several reasons they want nothing to do with her. That conversation ends with Barbie crying.

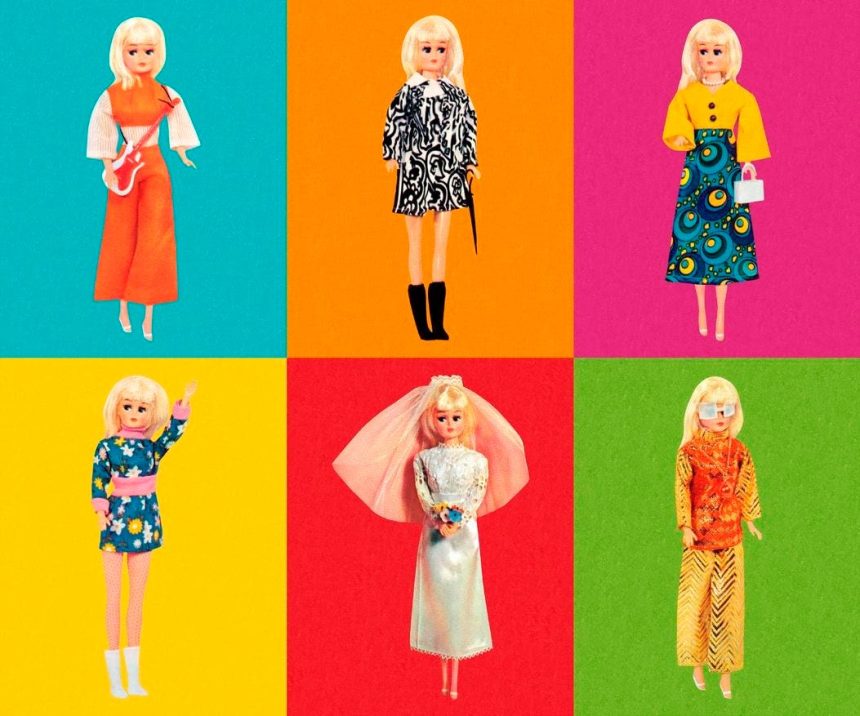

Barbie was a doll invented in 1959, infused (perhaps unknowingly) with the beauty values of an era when women didn’t have access to the birth control pill yet and before they could even have their own credit card. The Voting Rights Act wouldn’t be passed for another six years. The Jim Crow era hadn’t even ended. To see Barbie re-emerge in 2023 at the center of a critique of gender roles is, sort of, gobsmacking. Yet, I understand it. In this film, I knew that Barbie was a stand-in for all the people who couldn’t seem to figure out what cultural appropriation was, the people who asked inappropriate questions to queer and trans people, the people who have responded to the human rights demands of the body positivity movement with the question, “But what about health?” and the people who didn’t adopt feminism or anti-racism until the absolute last possible moment. If we can accept Barbie now that she’s come around, then we can forgive all those people too. I’m mad at the way the Barbie movie becomes yet another well-funded media project that’s ultimately designed to humanize and exonerate the Barbies of the world, but I also understand the importance of feeling that redemption is possible for all of us.

Humans tell the same stories again and again so that we can connect across generations and learn the lessons and symbols that are important to societies and the people who comprise them. How does a 9-year-old connect to a 90-year-old? Through a story like Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, or a character like Barbie. In the past, we often left problematic characters who couldn’t stand the test of time to wilt in the harsh and unforgiving sunlight of our social awakening. If they did re-emerge, they were often silently revamped as if the past had never happened. It gives me hope to see media that’s trying to grapple with massive issues, like racism, sexism, and fatphobia.

The Barbie Movie confirmed the sense that we as a culture are craving both accountability and reconciliation, pathways to keep human relationships intact even after wrongdoing has been committed. This is a deeply hopeful project, but it requires an honest accounting of the damage that has been done.

Read the full article here