The Super Bowl is advertising’s biggest stage—and an expensive one, at that.

This year, it cost advertisers up to $7 million for 30 seconds to appear in the national broadcast, and that’s just to get it on the air. These days, Super Bowl advertisers are often encouraged to shell out for a celebrity, but not someone who could outshine the brand. The ad is expected to meet other requirements, like getting people’s attention, keeping it, and encouraging them to act. Maybe it should make them laugh. Maybe it should make them cry. In other words, it’s got to be perfect. Better not mess it up.

“The pressure on the marketing team that’s behind it all is huge,” Kerry Benson, creative solutions lead at Kantar, told Marketing Brew. “There’s just a lot at stake. It gets highly scrutinized by not just consumers, with things like the USA Today [Ad Meter]…We all know that the Super Bowl isn’t just a 30-second ad anymore; it’s a campaign in and of itself.”

There’s no guarantee a Super Bowl ad will exceed—or even meet—consumer expectations, but we asked a few Super Bowl ad experts what tactics they have seen lead to success, and which ones they think are more likely to flop.

(Not so) secret sauce

Generally speaking, it’s hard—but not impossible—to go wrong combining star power with humor, according to Jason Harris, co-founder and CEO of creative agency Mekanism, which has worked on about a dozen Super Bowl ads. Kantar’s Benson concurred, adding that in any given year, about 70% of Super Bowl ads feature celebrities.

Rick Suter, a senior content strategist at Gannett and editor of USA Today’s Ad Meter, said “SNL power,” aka working with people who are famous and funny, has proven effective since the early days of the Ad Meter. The first-ever win in 1989, for instance, went to an American Express ad that starred comedians Jon Lovitz and Dana Carvey.

But brands run the risk of being forgotten if they’re overshadowed by stars, Benson said. To minimize that possibility, she said advertisers could consider casting celebs who have authentic connections to their brands. Two recent examples Benson pointed to: Dexcom, which makes continuous glucose monitoring systems and has worked with Type 1 diabetic Nick Jonas, and Massachusetts-based Dunkin’s work with Ben Affleck.

Other execs advised that advertisers make sure their brand, not the celebrity, is the star of the show. “For it to be an effective spot, and for it to really make a difference, you still have to sell something,” Harris said. “A lot of time, the brand will get lost or overshadowed by the celebrity or the gag. You have to make sure that the brand is front and center.”

Get marketing news you’ll actually want to read

Marketing Brew informs marketing pros of the latest on brand strategy, social media, and ad tech via our weekday newsletter, virtual events, marketing conferences, and digital guides.

Mekanism’s 2013 ad for Pepsi promoting Beyoncé’s halftime show, for instance, was well-received, according to Harris—not because of the Beyoncé song in the background, but because it was “clever,” “unique,” and focused on the brand being advertised, which was obvious from the start.

Hard feelings

Some brands wait until the very end of their Super Bowl ads to reveal themselves. Benson advised against that, saying that it indicates that “the brand doesn’t play the starring role in the story that the ad is telling.”

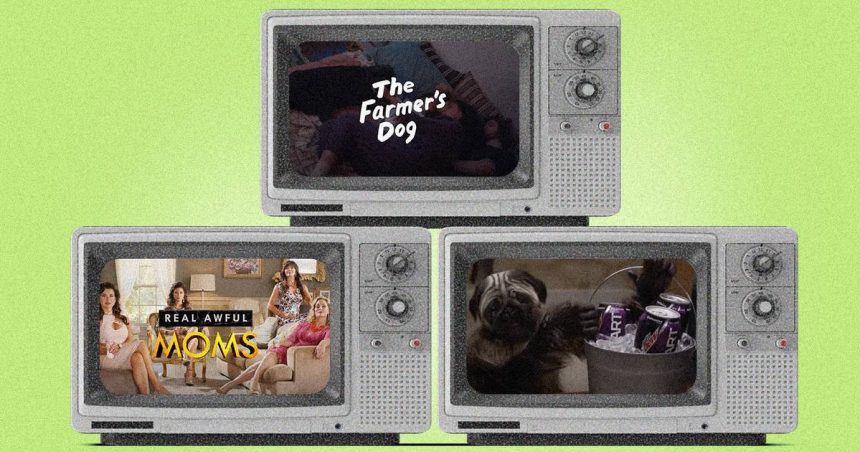

Making fun of things people love may also miss the mark, Harris advised. He learned this from experience: Mekanism was behind the “Real Awful Moms” ad for online game World of Tanks in 2017 that poked fun at the Real Housewives franchise (and didn’t include any celebs). Some might say it tanked: The spot scored a 3.95 on the Ad Meter, the lowest-rated ad that year.

Tugging on the heartstrings can also be risky. “What doesn’t work at the Super Bowl is going emotional,” Harris told us, noting that most people watch the Super Bowl in a group setting and would rather laugh than cry in public. There are some exceptions: Last year, The Farmer’s Dog topped the Ad Meter with a real tearjerker. But that ad featured a dog, and dogs and babies tend to do well in Super Bowl spots (and in real life), Harris said.

In rare cases, marketers might be able to get away with poking fun at the typical Super Bowl ad formula itself, and Harris and Suter both pointed to Mountain Dew’s 2016 spot, “Puppy Monkey Baby,” as a success. Advertisers can try to break that formula, too, like in Oatly’s 2021 ad that starred its CEO, or Coinbase’s QR code spot from 2022, but it can be risky, they both said.

While Super Bowl ad stakes are high, there is perhaps one comforting insight thanks to social media, at least for those marketing teams that look to buzz as a metric of success: All press is good press, or so the saying goes.

“You could make an argument that there are no bad ads anymore, because even the worst ones kind of stand out,” Suter said. “People are talking about it.”

Read the full article here